Hegel: The Realization of Moral Instruction via Folk Religion

Note: This is an essay I wrote for Prof. Karen Feldman’s German 157 Luther, Kant, and Hegel course at UC Berkeley in Fall 2021. I want to thank Prof. Feldman for her discussions and feedback throughout this process.

In Hegel’s “The Tübingen Essay”, Hegel proposes the importance of folk religion, which itself is constituted “with respect to ceremonies” (49). This communal and sensual approach contradicts Kant’s argument of a moral religion derived from individuals’ rational reasoning, which Hegel disagrees with. However, this also seems to deviate from German Protestant (particularly Luther’s) thoughts’ de-emphasis on rituals, which is often deemed as too Jewish or Catholic. Thus, does Hegel deviate from Luther’s “sola fide”? I aim to explore this apparent deviation and show that Hegel’s reasoning and solution of folk religion not only is harmonious with Luther’s ideas of “love and faith”, but also is necessary to mediate the tension of synthesizing moral instruction with Luther’s model of Christianity.

What is Hegel resolving?

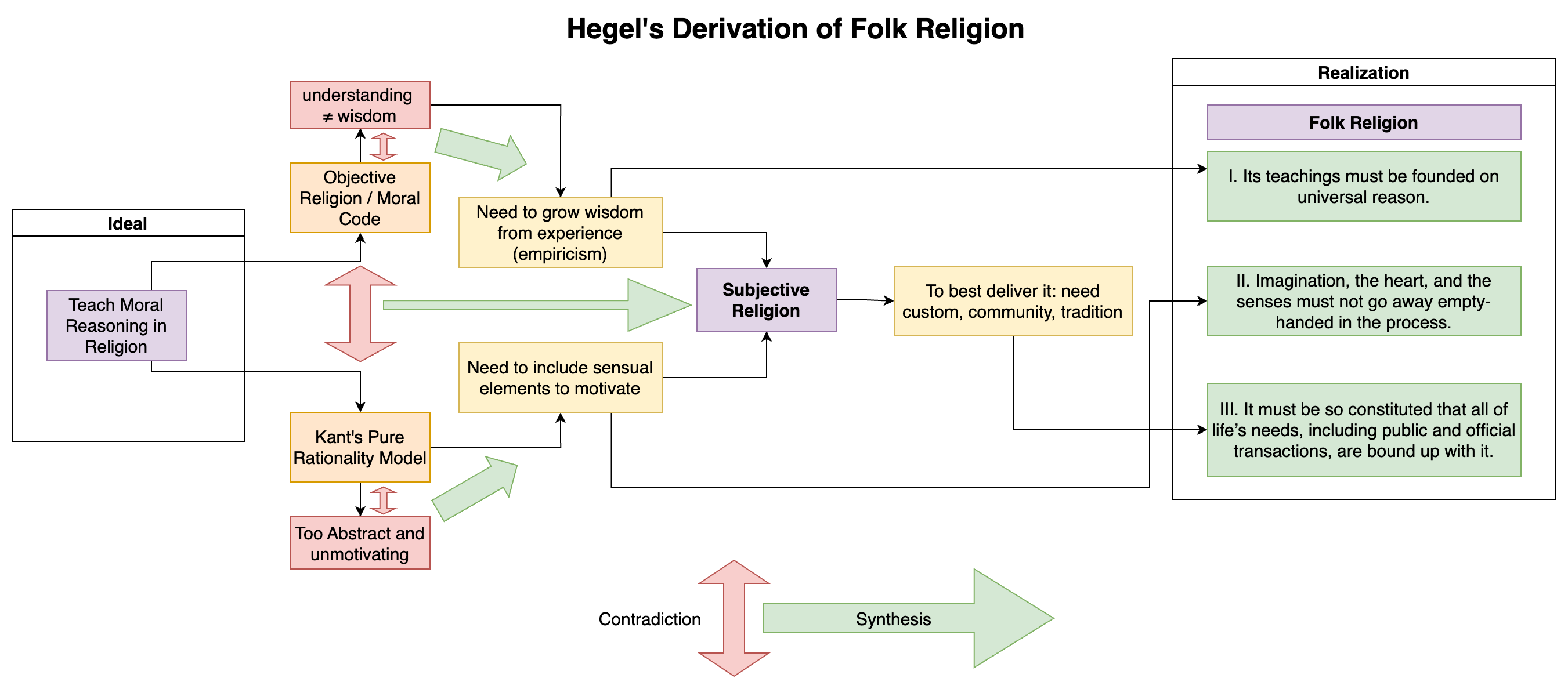

To see the deviation, we must first recognize what is Hegel trying to resolve. Hegel aims to synthesize Christianity with rational enlightenment and moral instruction, in particular, a mostly Kantian model of moral reasoning, although Hegel does not explicitly mention Kant in The Tübingen Essay. For context, Kant emphasizes that one should act in accordance with pure rational reasoning, and Christianity is the true moral religion that allows teaching “Of the way they would of themselves voluntarily act if they examined themselves properly.” (Religion and Rational Theology, 230) Hegel sees issues with “examining themselves properly”, especially because “reason as such seldom reveals itself in its essence” (The Tübingen Essay, 31). It is important to realize that Hegel does not disagree with Kant in that moral instruction should be delivered and rationality needs to be cultivated in individuals, but rather how morality shall be derived and taught.

What does Hegel disagree with Kant’s model?

As mentioned above, Hegel describes Kant’s model of reasoning and morality as being too abstract, “to separate in abstracto pure morality from sensuality and make the latter more subservient to the former.” (The Tübingen Essay, 31) Reasoning cannot be separated from sensuality as a realm by itself, because Hegel believes that “sensuality is the predominating element in all human action and striving.” (The Tübingen Essay, 31) Instead, Hegel reveals that reasoning blends into our sensual life and action, “ideas of reason animate the entire fabric of our sensual life and by their influence show forth our activity in its distinctive light” (The Tübingen Essay, 31); just like light animates objects, salt brings out the flavor of food, moral reasoning is always sprinkled across our actions but one cannot isolate it via Kant’s model of pure rational reasoning.

More dangerously, Hegel points out that “other people are deaf to the voice of duty; it is quite useless to try to call their attention to the inner judge of actions which supposedly presides in man’s own heart…. self-interest is the pendulum whose swinging keeps their machine running.” (The Tübingen Essay, 34); Kant’s model of each individual conduct their own moral reasoning breaks down here, for those who refuse to follow their duty. Even those who believe they are following their duty could mistakenly believe in their reasoning with “self-love, in which the ego is in the end always the highest goal.” (The Tübingen Essay, 47) Hegel points out that individuals’ own understanding is “ruled complaisantly by the moods of his master”, that sensuality does not allow us to think in a purely rational fashion.

Is Objective Religion alone feasible?

Kant hypothesizes that pure rational reasoning across individuals trends toward a universal and shared underlying morality, “the law, as an unchanging order lying in the nature of things.” (Religion and Rational Theology, 231) Well if individuals have a hard time conducting pure moral reasoning or overcoming their ego, could we create a shared fabric of morality and just ask everyone to follow it? Hegel calls that the objective religion, describing it as a “frozen capital” (The Tübingen Essay, 33), such as religious laws and systematic knowledge. Objective religion seems to capture Kant’s universality of morality, as Hegel describes that objective religion “can be the same for a large mass of people, and in principle could be so across the face of the earth” (The Tübingen Essay, 34), but these sets of “moral code” are acquired by an individual via reading them rather than internally derived by themselves.

Hegel is not satisfied with such a solution. Although moral codes apply universally to population, they could never cover all scenarios; thus for those scenarios uncovered, one is left with the same dilemma as before, of needing to reason by oneself and hence not necessarily truly moral; even if there are sufficiently extensive codes, remembering and consulting them every time would cause “eternally hesitant and at odds.” (The Tübingen Essay, 40)

Another key distinction is that Hegel believes that this form of “understanding” is separate from “wisdom.” Hegel gives the example contrasting Louis XIV’s ignorance for the details of the Palace of Versailles, versus a family man who knows the detail of his family home. Hegel praises the latter as that wisdom is built by oneself, through empiricism, whereas Versailles represents understanding although “becomes gradually more extensive and complex, it becomes less and less the property of any one individual,” (The Tübingen Essay, 45) hence less and less relevant for one to use when moral reasoning is needed upon.

Sensuality is Key and Subjective religion is in line with Luther

So far, we discussed the limitation of the pure rational reasoning Kant proposed, “a universal church of the spirit remains a mere ideal of reason,” (The Tübingen Essay, 45) as well as objective religion’s inability to effectively guide individuals throughout the complexity of life or equip one with true wisdom. It is worth pointing out Hegel’s opposition to those two proposals closely align with Luther’s opinion. Similar to Luther disliking the extensiveness of the Jewish laws and hence is impossible to follow, Hegel points out there is not a set of comprehensive moral codes one can possibly follow for every action they perform; thus he is also looking for something more inward and individualized. Just as Luther believes that human nature is evil and no laws can prevent that, Hegel states “no printed code or manner of enlightening the understanding could ever prevent evil impulses from taking root or even flourishing”. (The Tübingen Essay, 40) As a solution, Luther provides “Grace” and “love and faith” to overcome the shortcoming of human nature and law’s ineffectiveness, Hegel turns into incorporating empiricism, or subjective religion.

Subjective religion, like Grace, is always alive and individualized. To counter the potential evil and ego influencing our sensuality and stopping us from making rational decisions, Hegel counters the pitbull of sensuality with sensuality, as “it sets up a new and stronger dam against the pressure of sensual impulses. But if religious motives are to have an effect on sensuality, they too must be sensual; hence among sensual people religion itself is sensual.” (The Tübingen Essay, 32) As God-given Grace counters natural evil impulses, subjective religion aims to overcome our own sensuality not with reason but with stronger sensuality.

Corresponding to Luther’s “love and faith”, Hegel has his own rendition of those terms in the context of reaching truly moral decisions. For love, “Forgetting about itself, love is able to step outside of a given individual’s existence and live, feel, and act no less fully in others – just as reason, the principle of universally valid laws, recognizes its own self in the shared citizenship each rational being has in an intelligible world,” (The Tübingen Essay, 46) Hegel incorporates Kant’s categorical imperative, which makes individual to consider their action in the context of others, and see if that action would reach consensus universality. This formulation also reconciles with the aforementioned pitfall of “self-love”, that one’s ego-driven understanding does not count as love, therefore, is immoral. For “faith”, Hegel portrays the motive of individuals as “prostrates himself before God, thanking him and glorifying him in all that he does…. motivated also by the thought: This is pleasing to God – which is often the strongest motive.” (The Tübingen Essay, 33) With faith acting in accordance with God, this formulation brings in God to be “fully present in the world as spirit” (An Introduction to Hegel, 249), thus that one is always operating with the ultimate moral reasoning. With these principles, Hegel concludes that the subjective religion acts in our sensual lives, “with all the force of its teaching might be blended into the fabric of human feelings, bonded with what moves us to act.” (The Tübingen Essay, 36)

Folk Religion: the Gateway to Cultivating Subjective Religion

Now that we have seen Hegel’s formulation of subjective religion is so tightly in line with Luther’s rendition, we must examine the apparent deviation that started our discussion. Why does Hegel bring up the concept of a Folk religion, that emphasizes tradition and exterior worship (both of which Luther disapproves)? As we concluded, to deliver moral instruction, “the purer tenets must be coarsened and given a more sensual exterior if they are to be understood and made accessible to a sensual disposition.” (The Tübingen Essay, 42) Folk religion via ceremonies give individuals an external boost of their sensuality, “Through the mighty influence it exerts on the imagination and the heart, folk religion imbues the soul with power and enthusiasm, with a spirit indispensable for the noble exercise of virtue.” (The Tübingen Essay, 47). In addition, to keep subjective religion as a long-living active spirit, “customs must be introduced that require., if one is to be aware of their necessity and utility, either trusting belief or habituation from childhood on” (The Tübingen Essay, 42), because religion customs have a binding force to keep and remind one of commitment to God, “from our belief that God demands them of us as being appropriate and obligatory” (The Tübingen Essay, 42). Hegel recognizes the danger of his emphasis on customs could be misunderstood as a direct contradiction with Luther, thus he emphasizes without the faith that those customs do honor to God, “despite their edifying effect, thereby already lost a good deal of their potential impact on me.” (The Tübingen Essay, 42) Just as for Luther an act of good could both come from God’s Grace and human will but only from Grace is good, Hegel emphasizes that the intention of performing the ceremony is much more important than the form itself.

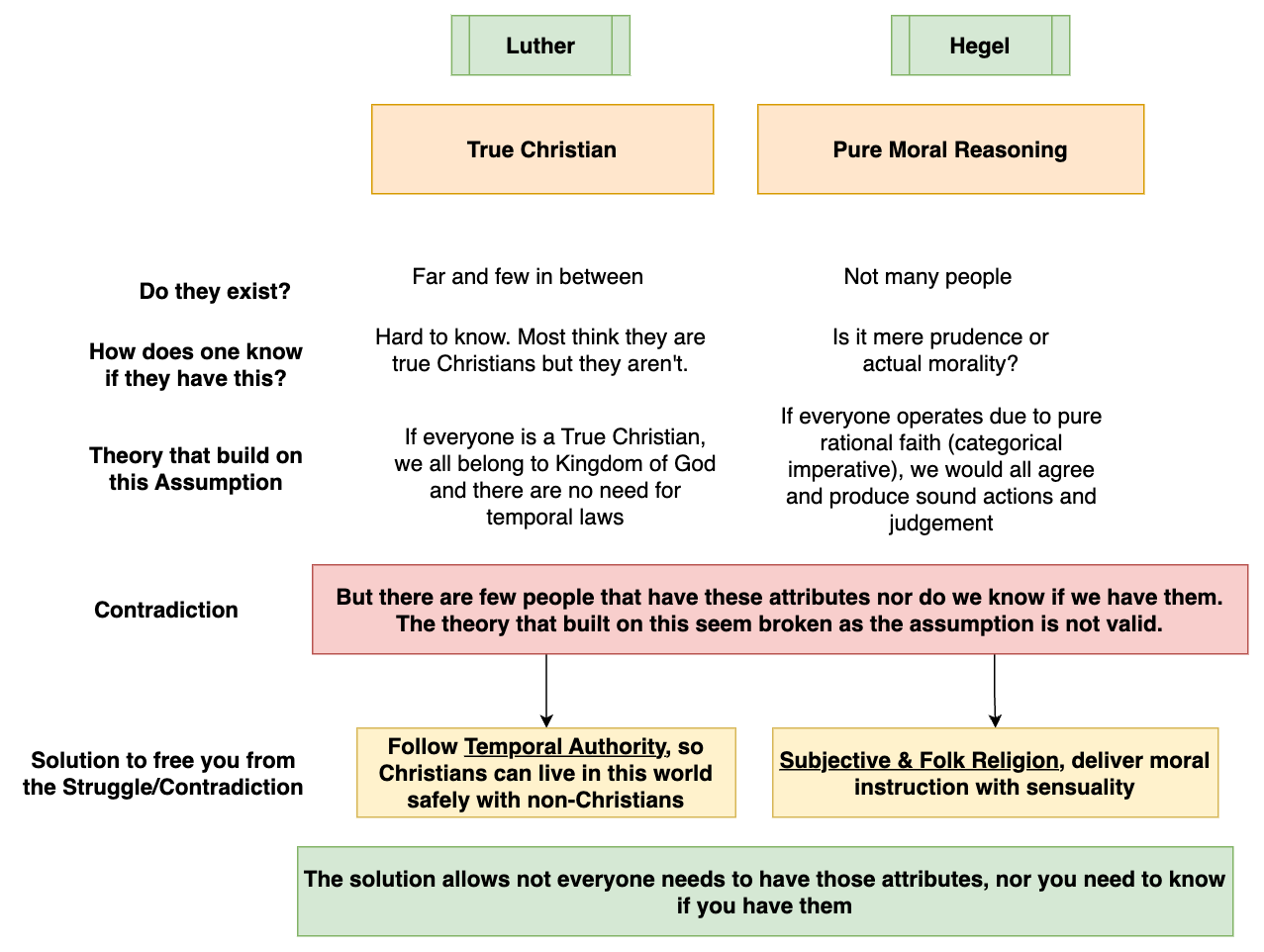

Parallel with Luther’s Method

Not only does Hegel not contradict Luther, Hegel’s approach to explain and propose the concept of Folk Religion is surprisingly similar to Luther’s depiction of “temporal authority” (more context about that in my essay on that). Similar to Luther acknowledging that there might be very few “True Christians”, or is hard for one to know is oneself is one, Hegel also states that “by alluring description of wise or innocent men, as to ever hope to find very many such people in the real world” (The Tübingen Essay, 31); there are few people that might reach the true moral principle Kant proposes. In addition, it is hard for one to know if one is acting according to true moral principle, “no easy matter to tell whether mere prudence or actual morality is the will’s determining ground.” (The Tübingen Essay, 31)

This inherent uncertainty causes the theory that relies on them to seem unreasonable, such as Luther’s Kingdom of God and Kant’s Categorical Imperative. However, Luther and Hegel both provide solutions that free one from this uncertainty. For Luther, whether one is a True Christian or not, as long as we all follow temporal authority in the secular sphere, non-Christians and Christians can live in peace. For Hegel, whether one is capable of conducting pure rational reasoning, as long as one practices subjective religion through the participation of folk religion, one would act according to sensuality but with the ultimate moral reasoning sprinkled subtly within it due to faith in God. Hence, with these renditions of “faith and love”, Hegel has found the solution that “if we but know how to calculate well enough, the results will outwardly appear the same as when the law of reason determines our will.” (The Tübingen Essay, 31)

Conclusion

Throughout The Tübingen Essay, Hegel via a series of dialectical arguments described how moral reasoning could be taught, moving from an abstract ideal towards practical implementations. Although the end solution, folk religion, appears to be against the common trope of German Protestant thought, the reasoning behind is deeply rooted in the tradition of Luther’s epistemology. As Hegel concludes, “because our duties and our laws obtain powerful reinforcement by being represented to us as laws of God, and in part because our notion of the exaltedness and goodness of God fills our hearts with admiration as well as with feelings of humility and gratitude.” (The Tübingen Essay, 32) The inconclusiveness of moral codes (objective religion) calls out the emphasis on sensuality, thus proposing the idea of subjective religion. By re-formulating Luther’s love and faith in the context of moral instruction, Hegel also reconciles with Kant’s categorical imperative in the concept of love, while relieving the burden for one to reason by incorporating faith. Ultimately, Hegel’s folk religion is to “weave these fine strands into a noble union suitable to his nature,” (The Tübingen Essay, 47) by assisting the subjective religion with the supply of sensuality and enthusiasm with customs and community. Though it might appear contradictory just like Luther’s temporal authority did, the reasoning behind it is still consistent; that is what I found most surprising about Hegel’s argument, able to resolve the inherent tension of teaching moral reasoning with religion, while relieving the burden of Kant’s demanding moral reasoning from individuals.