Temporal Authority: Contradiction or Unification

Note: This is an essay I wrote for Prof. Karen Feldman’s German 157 Luther, Kant, and Hegel course at UC Berkeley in Fall 2021. I want to thank Prof. Feldman for her discussions and feedback throughout this process.

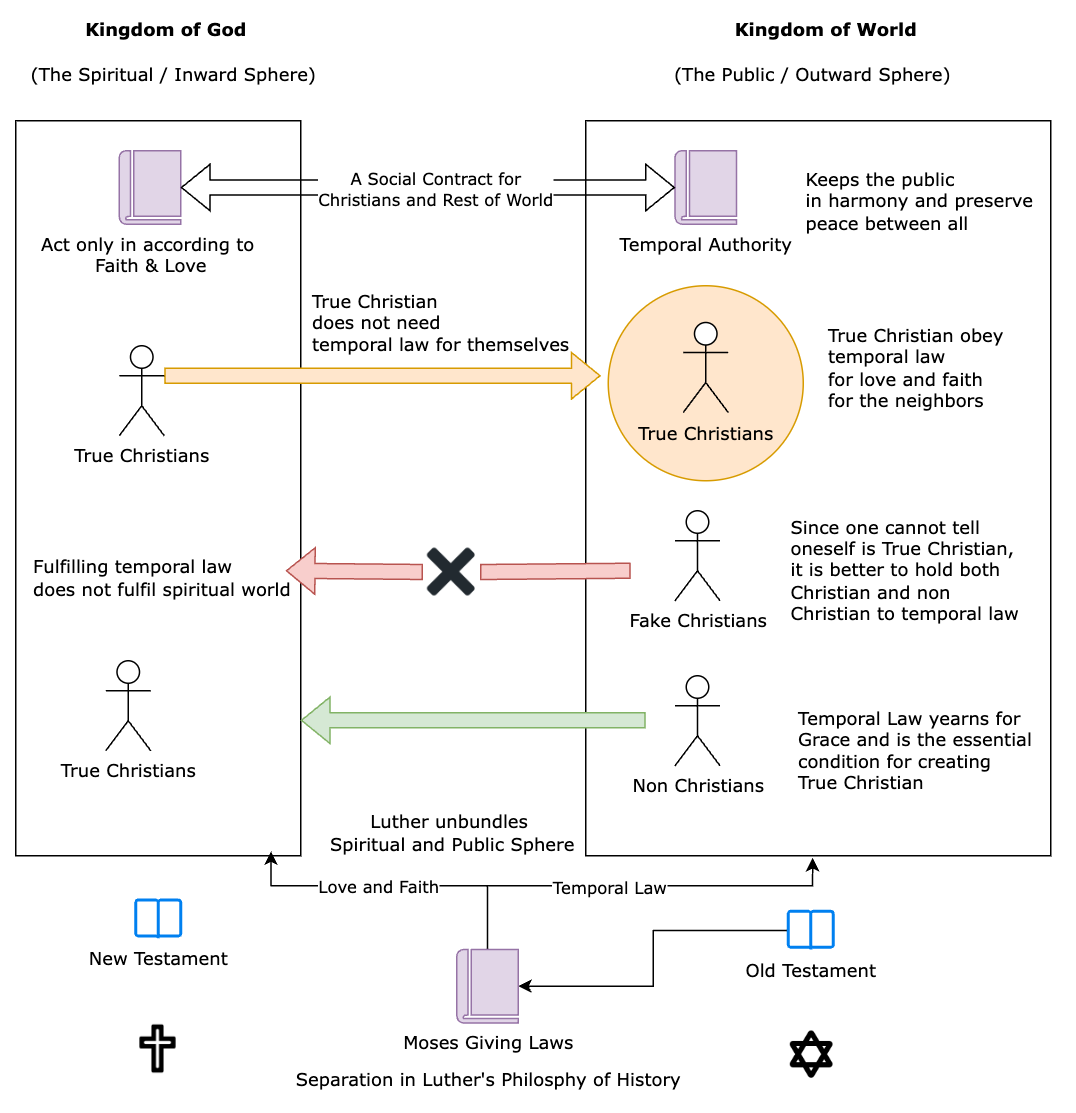

In Prefaces to the Old Testament, Luther explains the causes for the extraneous laws in the Old Testament, showing the impossibility to obey laws leads to the yearning for God’s Grace. Thus, for Christians, faith matters more than following laws; in particular, “Faith and love are always to be the mistresses of the law and to have all laws in their power” (Preface to the Old Testament, p.14). However, Luther in Temporal Authority points out that “True Christians”, although do not need laws, should follow the extensive set of temporal laws. There seems to be a contradiction: if only “faith and love” matters, why shall Christians still follow temporal laws? I believe the contradiction does not stand; rather, following “faith and love” justifies temporal laws in Luther’s rendition. I aim to examine through the lens of separating the outward and inward sphere, unbundling Moses’ Laws into spiritual and temporal, and how ultimately temporal laws present a unifying resolution and social contract between Christians and non-Christians.

Let us examine what seems to be the contradiction. First, one must understand that what Luther means by the laws and their purpose. Luther points out the three types of laws in the Old Testament: temporal laws, laws about external worship, and “over and above these two are the laws about faith and love” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 123). Moses’ instructions cover all three of these types, with extensiveness that Luther calls “goes so far that some of the prescriptions are to be regarded as foolish and useless” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 122). Despite that, Luther still calls Moses the “perfect lawgiver” (Prefaces to the Old Testament,p121), where his extensive set of laws make others aware of sin, as “laws cause only sin and wrath” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 123), and make them “recognize their illness and their dislike for God’s law”, as it becomes impossible to follow all these laws, hence “also long for grace” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 124).

With the New Testament and the power of Grace to fulfill these laws, Luther sees there is no further need to follow laws in such detail. This is because some of Moses’ laws create “sins of things that are in their nature not sins, (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 126), such as eating leavened bread at Passover. Luther believes those laws can be “done away” as “they became sins only because they are forbidden by the law.” Luther goes even further saying as Christians, the only laws needed beyond the Ten Commandments, are “faith and love”, as all laws are valid only if they don’t conflict with “faith and love”, otherwise they can be done away (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 123).

In Temporal Authority, Luther urges Christians to follow all laws created by temporal authority, such as imperial laws, and act in accordance with political authorities. Though he claims true believers “need no temporal law or sword” (Temporal Authority, p. 663) as the Holy Spirit and God’s Grace guides them to righteous acts, that of “much more than all laws and teachings can demand.” However, if Luther claims the only laws a Christian should follow are “faith and love” and they do not require the law as the Grace operates through them, why shall one still follow temporal laws? This becomes even more problematic as in Disputation against Scholastic Theology, Luther claims: “Condemned are all those who do the works for the law” (No. 79). By explicitly following temporal laws, it seems that Christians are acting with their own will as they do not require those laws in the first place. Suggesting Christians to strictly follow laws also contradicts his criticism of Judaism, “the Jews are greatly in error when they hold so strictly and stubbornly to certain laws of Moses” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 123). So why shall Christians submit and follow all the laws given by temporal authority? Shouldn’t they only follow “love and grace” or use their own judgments, and choose to disobey laws that can be done when it is in conflict of “love and grace”?

In Luther’s rendition, there is a clear distinction between the outward and inward sphere, which can be characterized as public versus spiritual, “God ordained the two governments, the spiritual, …, and the temporal, …” (Temporal Authority, p. 665). This is almost a secular formulation, where the Kingdom of God has only Christians and the Kingdom of World that includes non-Christian. The two population has different behavior and nature of will. As Luther described in the Disputation,“without the grace of God the will produces an act that is perverse an evil” (No 7), hence the non-Christians are destined to commit sinful acts, whereas the Christians won’t as “conform in every respect to the will of God”, thus they act in according to Grace. “A good tree needs no instruction or law to bear god fruit; its nature causes it bear according to its kind without any law or instruction” (Temporal Authority, p. 663), it seems that Christians do not need instruction or law at all.

The temporal laws are clearly only created to restrict the non-Christians in the Kingdom of Wolrd formulation to “keep still and to maintain an outward peace” (Temporal Authority, p. 665). Luther is illustrating the Kingdom of World as a public sphere, where the objective is to keep the peace and prosperity of the collective. He then suggests True Christians follow temporal laws as “such service in no way harms him, yet it is of great benefit to the world” (Temporal Authority, p. 668). One does so not for oneself, but for one’s neighbors, “he concerns himself about what is serviceable and of benefit to others” (Temporal Authority, p. 668). Thus, this formulation of serving the public sphere successfully resolves the question earlier, that one follows temporal law is in fact in accordance with “faith and love” for others. Rather than pure performative acts from one’s own will, obeying temporal laws became “duties of his own calling” (Temporal Authority, p. 668), and hence is righteous and one must follow.

This framing also does not contradict Luther’s guidance of following laws flexibly in Preface to the Old Testament. He claims laws shall be kept or omitted by Christians depends on whether they necessarily act according to “faith and love”, but “if it were necessary or profitable for the salvation of one’s neighbor, it would be necessary to keep all of them” (Temporal Authority, p. 671). Hence, to tell Christians to follow temporal laws is not blindly following pre-defined laws, but rather for the necessity to align with “faith and love” and others’ needs, let it be temporal laws or disobeying them. When one is aware of misalignment between the ruler and “faith and love”, Luther says men must not follow the ruler as one must obey “God (who desires the right) rather than men” (Temporal Authority, p. 671).

In addition, temporal authority is the necessary and essential condition to produce “True Christians”. Luther claims “since no one is by nature Christian or righteous, but altogether sinful and wicked” (Temporal Authority, P 664). For the wicked ones, they do not realize their sins unless there are laws, “if there were no law, there would be no sin” (Preface to the Old Testament, p. 125). In that sense, the temporal authorities take on the same responsibility as Moses being the lawgiver to make others aware of their sinfulness. “The unrighteous do nothing that the law demands; therefore, they need the law to instruct, constrain, and compel them to do good” (Temporal Authority, p. 663). Thus, with the conflict of their natural will against the laws, they would yearn for Grace and be in the direction to become a True Christian.

Furthermore, just as one doesn’t know if they are acting via their own will or via the power of Grace, one can never know if they are a True Christian, evenly those who claim them to be one, “Christians are few and far between” (Temporal Authority, p. 665). In addition, he doubts anyone always acts in God’s will, “since in this life the Spirit is not perfected and grace alone cannot rule” (Preface to the Old Testament, p.119-120), as one could deviate from the realm of truly Christian from time to time. However, in Luther’s rendition, regardless if one is Truly Christian, permanently or temporarily, they all act according to temporal authority, although for different reasons. Thus, temporal authority unifies the end behavior and could be applied universally.

With its universal applicability, temporal authority acts as a social contract between Christians and the rest. As True Christians are instructed to “do not resist evil” (Temporal Authority, p. 669), Luther counts on the secular sphere to protect Christians to settle justice and keep the peace. In return, Christians obey and participate in the duties of temporal authority for the greater good of society. This collectivist approach could be seen in Luther’s explanation of how Christians “undoubtedly slew people for the sake of preserving peace” (Temporal Authority, p. 673) even for the Pagan and famously anti-Christian emperor Julian. Hence, Christians contribute to society’s necessary functioning in a flexible manner, as long as it is for the collective good, “for love pervades all and transcends all; it considers only what is necessary and beneficial to others and does not ask whether this is old or new” (Temporal Authority, p. 672).

This also explains Luther’s repeated mentioning of David not killing Joab who deserves death, to prevent “causing even greater damage and tumult” (Temporal Authority, p. 698). Hence, we see Luther’s “love and faith” is not for following absolute justice, but for the greater good of society. This is in line with the Christian philosophy of turn the other cheek instead of life for a life as said in the Old Testament. This social contract does not prevent “you suffer evil and injustice”, but with the collective and secular contribution, allow “yet at the same time you punish evil and injustice”. The duality of the worlds and Christian following temporal authority allows for “you do not resist evil, and yet at the same time, you do resist it” (Temporal Authority, p. 670).

There have been various controversies regarding Luther’s seemingly contradictory view of authority, famously because Luther led the Reformation against the Catholic Church and priestly authorities; he inspired the German Peasant Rebellion yet crushed them by supporting the nobles. Granted that Luther is not a philosopher, nor does he ever claim to be one. However, from his writings alone, I believe there is no such contradiction, and temporal authority proposed a unifying and consistent framework that supports his other arguments. By separating Moses’ mixed laws into the ones about love and faith, and ones about temporal restrictions, Luther separated the sphere of spiritual and state. What is remarkable about temporal authority is that not only acts as a necessary agent for non-Christians to realize sins and yarn for Grace, as well as serves as a social contract for the secular state to protect the Christians as Christians do not aim to revenge evil personally. This collective system allows peace and harmony of Christians and non-Christians, as well as “at one and the same time you satisfy God’s kingdom inwardly and the kingdom of the world outwardly” (Temporal Authority, p. 670). His framing also leaves room for flexibility and ambiguity of one’s cognition of being True Christian, justifying the same resolution regardless of faith, yet always consistent with acting in “love and faith”. This unbundling and construction of separate spheres could be viewed as a resolution using Hegel’s Dialectic framework, where Luther resolved the tension of Christians following ideal yet need to survive in this world, which is a necessity for the Reformation movement as religion and political power are no longer tied as in the case for the Catholic Church.